Digital Art: Mike Rendel

The Impact of a Warm Midwest Winter

A retrospective originally published in January 2024 in the MWV blog.

Story By: Sara Wesche

“Stick season” is a colloquial term used in Vermont to describe the period between when the last of autumn’s brilliant foliage drops and before the white snows of winter settle in. Musician Noah Kahan recently brought fame to this term through his song. Characterized by its brown, gray, and earthy tones, stick season here in the Midwest, specifically in Michigan, where I am, has stretched well into December. It’s been unusually warm, with temperatures in the 40s to 50s. We could have comfortably had a “fall” bonfire on Christmas Eve. There hasn’t been more than a dusting of snow, and strangely, it’s been quite humid. It’s gloomy, gray, and somewhat sad. It’s unnerving.

It makes you wonder if the four seasons are fading away. For us, as a family of skiers, the lack of snow is downright frustrating. On the flip side, the absence of snow brings its comforts – easier driving, easier to get out of the house, and a more straightforward existence in many ways. It’s predictable. You don’t have to bundle up in snow pants and winter gear, nor take extra time for driving on slippery, snowy roads. But at the same time, I question whether these comforts are worth the consequences of what this might mean for the future.

Photo: Sara Wesche

Climate and Changing Winters

While I’m not a climate scientist or meteorologist, I have been a witness to Midwest winters for over four decades. I’ve lived in Michigan my entire life. While many things are cyclical, our winters are not what they used to be.

Does that make me sound old? Growing up in the 1980s, I remember winters starting right around Halloween. Snow was a consideration for your costume – you had to pick one that could accommodate moon boots or long underwear, or your winter snowsuit might need to fit underneath. And December was officially winter. We had snow, and we had deep snow. I remember my brothers digging giant igloos from the snow piles that formed on the corners of driveways and roads, the result of snow-blowing and snowplow trucks. Skiing at Christmas was the norm. We’d head Up North and rent one of those A-frame cabins that smelled of cedar and fireplace, a little damp, with dark wood and a stash of toys played with by generations of children. There was something magical about that time.

Perhaps the snow seemed more significant because I was smaller, but realistically, I think most would agree that our winters have become shorter over time. At best, it doesn’t arrive until well into December and often ends by early March.

Winter Memories and Future Generations

I wonder about the impact of these changes. Watching my son learn to ski and enjoy the winter months here in Michigan, I wonder how much is changing. I think about the mom-and-pop ski hills that rely on Mother Nature for snow. While many have invested heavily in snowmaking equipment, there’s something counterintuitive about it all being manufactured, though we’ll take what we can get. And this year, it’s been particularly evident. Even the UP and North Shore of Minnesota, some of the highest points in the Midwest, are without snow.

The independent ski hills of the Midwest hold a special place in the heart of the region’s skiing culture. These smaller, family-owned hills offer an experience vastly different from larger resorts. Unlike the commercialized resorts, they provide a more personal and nostalgic experience, focusing on the sport’s joy and connection with the natural surroundings rather than luxury amenities. Most began with simple means like a rope tow or a T-bar. Some still have just a single chairlift. They are places where generations have learned to ski, where local ski clubs meet, and where the spirit of community-centric winter sports thrives. However, these cherished local hills face extraordinary challenges as winters become milder and snowfall less reliable. Their struggle to remain open impacts the local economy and the loss of a vital part of the region’s winter culture and identity.

Photo: Sara Wesche

Buds are starting to form on the trees here. The grass is green and growing again. Our planting season has changed. Some say this is just a cycle, not climate change. I can’t help but disagree. And if this is the future, what does it mean in 5, 10, or 15 years? Do I even introduce my son to a sport that I love so much, that has been a part of our family history and the outdoor culture of the Midwest? What if these activities become relics of the past by the time he’s grown?

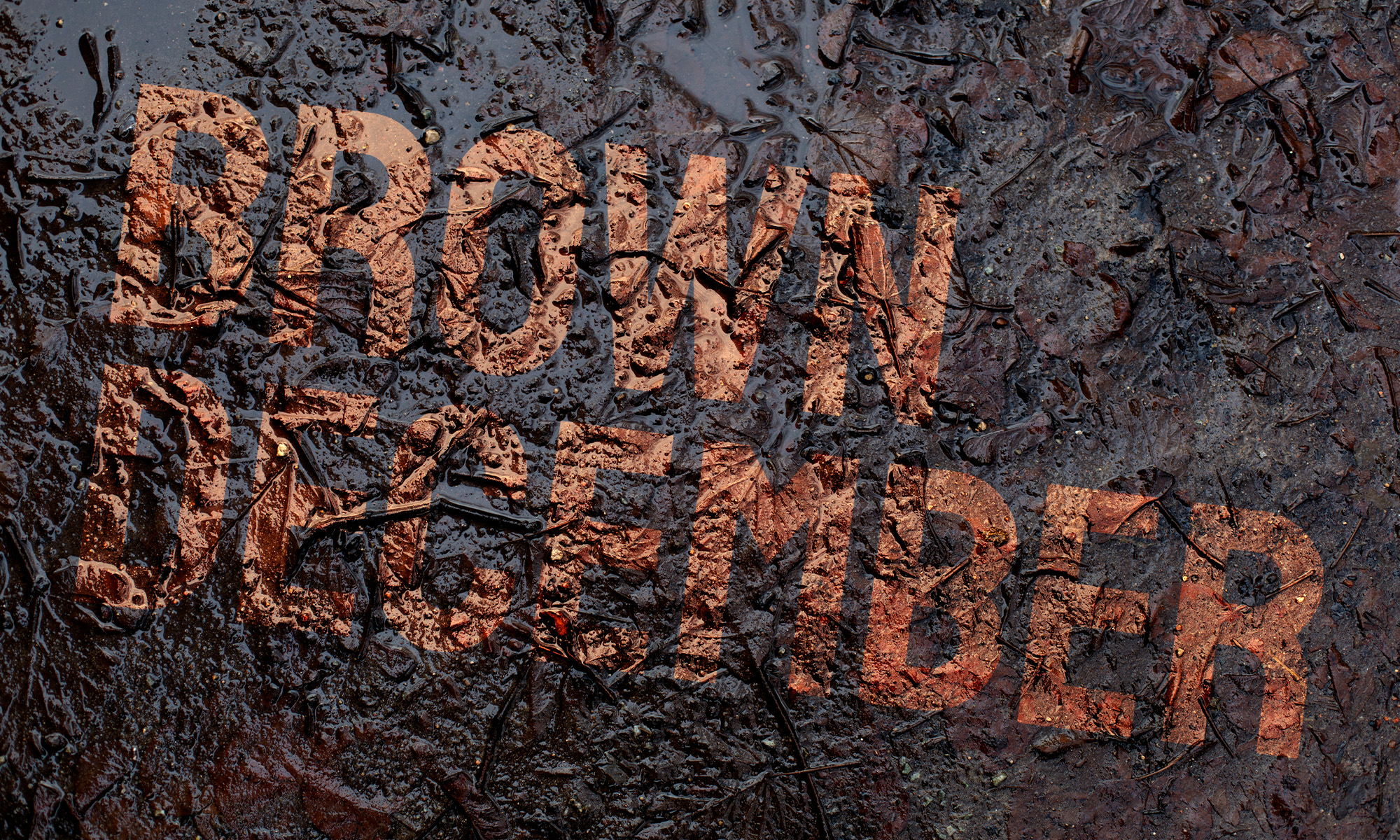

The Other Side of a Brown December

My climate fears aside, there is a strange allure to this temperate rainforest weather, with its subdued, earthy character. It brings a cozy, reflective feel. The setting is mysterious and otherworldly, inspiring a sense of wonder and tranquility. It feels like living in the Twilight movies or stepping out of an LLBean catalog. We’re so used to the harsh winter coming in fast and furious in late fall. Instead, this moody atmosphere highlights the understated beauty of the Midwest outdoors in a form that we usually don’t see. Amidst the grayness, the enduring colors become subtly more pronounced – the deep red of a cardinal, the gentle purples of berry vines. In their varied shades, the greens of mosses and ferns create a comforting, lush backdrop.

The woods are quiet. The usual rustling of wildlife is subdued, and the forest floor blanketed with fallen leaves muffles the footsteps of the few creatures that stir.

This is a stark contrast to the lively chatter of summer or the muffled hush under winter snow. Even during this unusual season, the Great Lakes exhibit a robust, untamed energy. The absence of ice allows the winter gales to churn the waters, stirring up waves that crash against the shores with impressive force – to the delight of the lake surfers. Though not overwhelming, these elements provide an inviting warmth to the landscape, offering a sense of calm and an appreciation for the more nuanced aspects of nature. There is beauty in all of this if you look close enough.

Photo: Sara Wesche

This isn’t to say that the relentless stretch of gray days and the unending expanse of brown ground profoundly impact one’s mental health. It’s a test of coping with the unexpected, finding small sparks of joy in a season without its familiar charm and vivacity. The short days are dark enough during these months. When there’s snow, it’s at least bright, even under gray skies. And it’s pretty. With our lake effect snow, West Michigan is like living in a snow globe. Cold temperatures and clear skies usually go hand in hand. When it’s below 20 degrees, we tend to have blue skies and sunny days, lifting everyone’s mood. While it is cold, it’s a cold you can escape by coming inside, not the damp cold that settles in your bones.

The changing face of winter in the Midwest, marked by milder temperatures and reduced snowfall, casts a shadow over the natural landscape and the region’s cultural and economic fabric. This evolving winter season challenges us to rethink our relationship with nature and the traditions we hold dear. Yet, amidst these challenges, there is an opportunity for resilience and innovation. Communities are finding new ways to come together, businesses are adapting with creative solutions, and individuals are rediscovering their connection with the outdoors in different forms. While the future of traditional Midwest winters remains uncertain, the enduring spirit of its people, their adaptability, and their deep-rooted love for their land continue to shine.