Photo: Mark Healey | Digital Art: Stephanie Thwaites

Meet Mark Healy

Midwest Lost Ski Areas Project

Story By: MWVJ Staff

Mark Healy was already 17 ski days deep into the season when we spoke in mid-December. He started the Saturday after Thanksgiving. When I reached out to schedule our chat, he let me know he skis every morning so our conversation had to fit neatly around his time on the slopes. In the winter, he skis 90 to 95 days a season, mostly at his “home hills” of Wilmot Mountain and Alpine Valley in Wisconsin—before hanging up his skis in the spring and switching to kayaking for the warmer months.

Mark is the kind of person you could talk to for hours and barely scratch the surface of his knowledge.

He’s a true gem of the Midwest ski community, a historian at heart, and the founder of the Midwest Lost Ski Areas Project (MWLSAP, www.mwlsap.org), a website dedicated to preserving the history of the region’s forgotten ski hills. His motivation? “Someone has to do it, or it’s all going to be forgotten.”

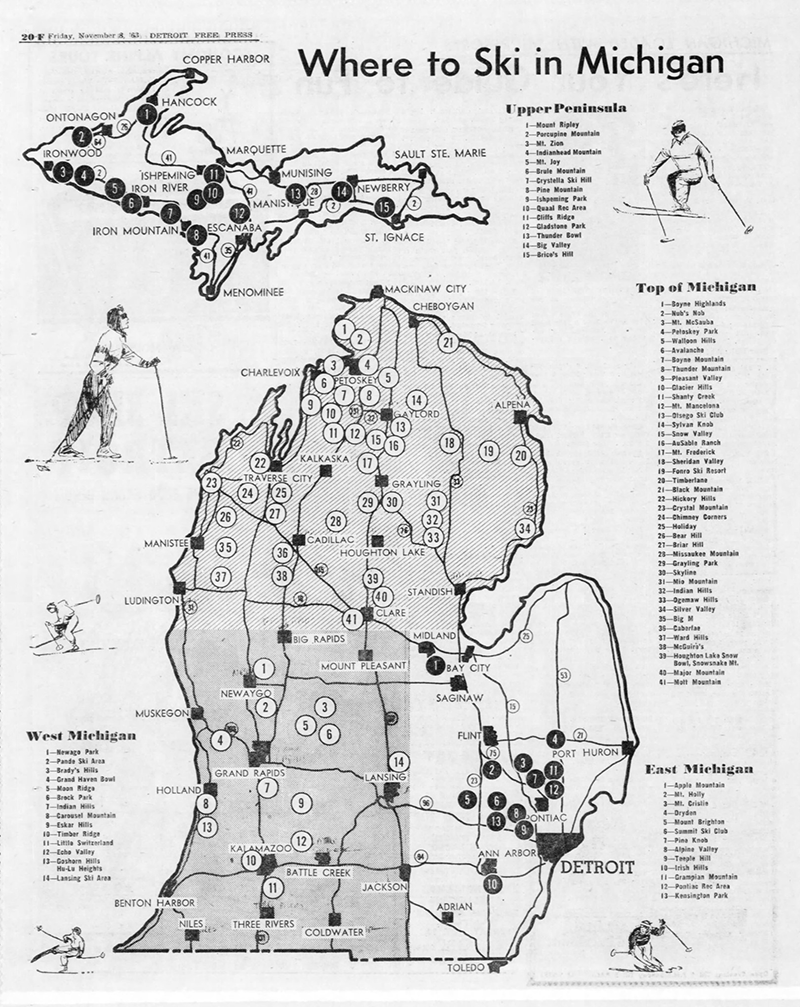

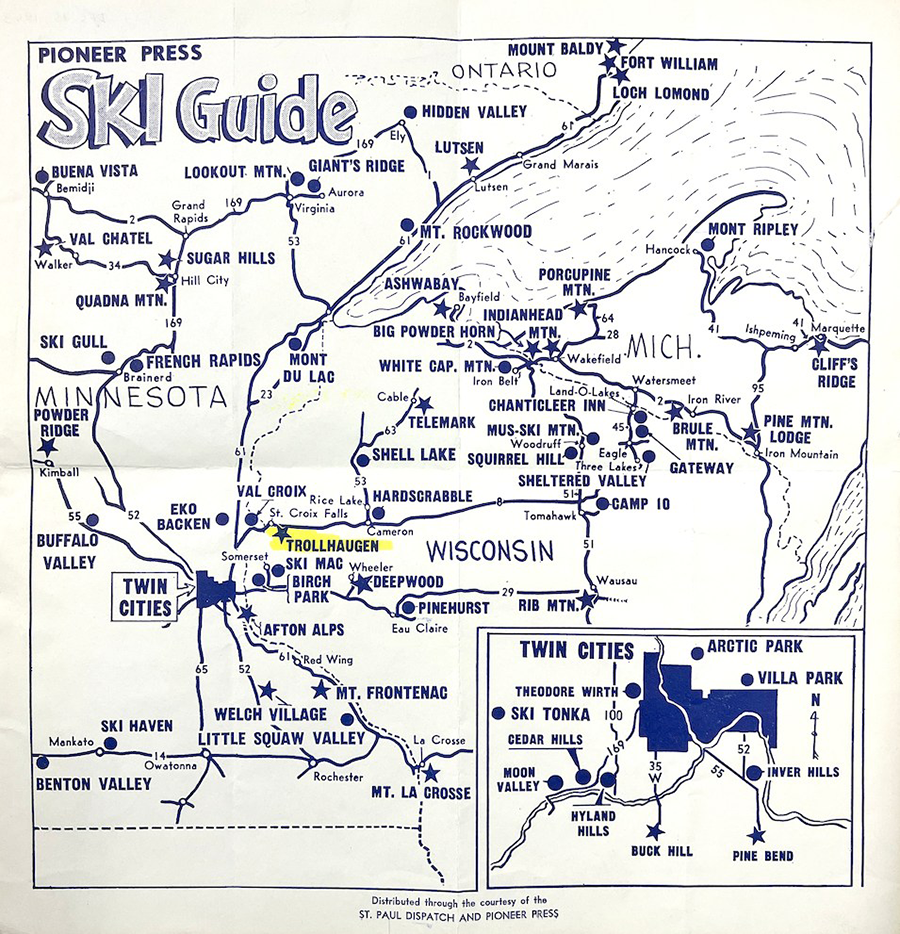

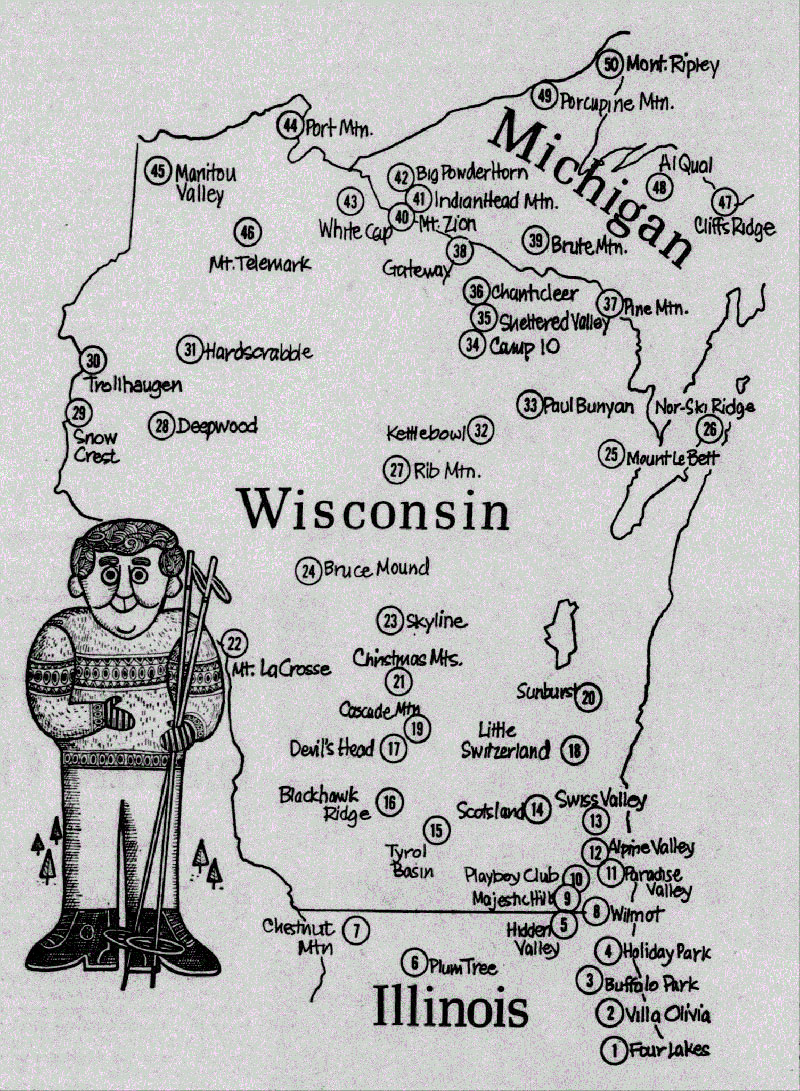

The idea took root in 2020 when Mark retired after 30 years of teaching economics at a community college in northern Illinois, where he still lives. He had dabbled in web design while helping his mother with the Red Lake County (Minnesota) Historical Society, and when he came across the New England Lost Ski Areas Project, he knew the Midwest needed something similar. So, he built it. MWLSAP is a treasure trove of lost ski hill histories, old maps, and archived articles—an evolving digital library dedicated to capturing what once was. He started by compiling lists of lost ski areas using an old ski area book from 1978, adding historical maps from Skimap.org, and referencing countless newspaper clippings. Over time, skiers, riders, and historians alike have contributed tips and stories, expanding the project into a rich archive of Midwestern skiing history.

Graphic: www.mwlsap.org

Graphic: www.mwlsap.org

Graphic: www.mwlsap.org

One of the more striking stories from his research is the ski hill in Wisconsin that was utterly transformed—hauled away, quite literally. When the ski area shut down, the land was converted into a gravel pit. Instead of a hill, there’s now a hole where skiers once carved turns. It’s a stark reminder of how quickly history can disappear if no one takes the time to document it.

Mark’s passion for Midwest skiing runs deep. He grew up in Red Lake Falls, Minnesota, just 90 miles south of Canada. His first turns were at Timberlane, a small ski area started by the Steiger Brothers, the same folks behind Steiger Tractor. His uncle owned the land the Steiger brothers leased for the hill and struck a deal: his nieces and nephews could ski for free. That changed everything. Mark was hooked, and the hill, open just a few days a week with four rope tows and all-natural snow, became his winter playground.

While Mark’s website is simple by design, its nostalgic, no-frills layout is almost part of the charm. “It’s more about making sure the history exists,” he told me. He spent hours poring over old news articles, tracking down lost ski areas, and connecting with local historical societies—some of whom didn’t even realize the ski hills existed in their towns. Many of these hills were modest operations, featuring just a few runs serviced by rope tows, embodying the grassroots spirit of Midwest skiing. Some of the stories he’s unearthed are downright unbelievable, even for a born-and-raised Midwesterner like me.

Take, for example, the University of Kansas’s Shocker Mountain, a rope tow that ran under their stadium for college ski classes. Or the ski jump competitions once held at Soldier Field, complete with hay bales lining the aisles and snow covering the seats. You could also ski there—they set up rope tows so skiers could ride from the field up the stands before making their descent. Mark summed it up with a chuckle, “They didn’t make any money, but what a good try.” And Devil’s Nest, Nebraska, a resort with chairlifts and lodges but no reliable snowfall, leaving the lifts standing frozen in time. The Midwest’s ski history is wild, full of ambitious plans, fleeting dreams, and entire ski hills that have literally been hauled away as gravel pits.

The Midwest has played a significant role in the development of skiing and snowsports in the United States. In 1841, miners from Beloit, Wisconsin, became the first people documented to ski recreationally in the U.S. The region also boasts the U.S. National Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame and Museum in Ishpeming, Michigan, recognizing its pivotal contributions to the sport.

Photo: Mark Healy

Mark loves the Midwest for what it is—a place where people make the most of what they have.

“When people tell me they only ski Colorado or out west,” he said, “I just shake my head and say, ‘I’m sorry for you.’ They usually ask why, and that’s when I tell them, ‘Well, you don’t ski very much, do you?’”

The truth is that Midwest skiing has a special kind of grit. You see the same people on the lifts all winter long, forming a tight-knit community that makes Midwest ski areas feel like home. Unlike sprawling resorts out west, where lift rides are often with strangers, here you get to know the folks riding next to you, running the same slopes time and again. Midwest ski resorts tend to foster a strong sense of community, with many being family-run operations that offer a warm, welcoming atmosphere where skiers and riders quickly feel at home. You drive hours to ski and ride because it’s worth it. And you find ways to make the most of the season, like hitting the terrain parks or learning to tandem ski with double bindings mounted on a long pair of skis, just as Mark and his son Lucas did. They even captured a video of their ride at Wilmot Mountain, Wisconsin. (P.S. – They once tried this at a well-known Colorado resort, but let’s just say it didn’t go over well with “management”.)

When I asked him what advice he’d give to someone looking for a place to ski, his answer was simple: “Go to the closest place and go often.” The Midwest is full of hidden gems—some lost, some still standing, all part of a history worth remembering.

You can find the Midwest Lost Ski Areas Project online at www.mwlsap.org and on Facebook.